I love editing. It’s unquestionably my favorite part of the filmmaking process. Yet it didn’t occur to me until recently that editing is the only craft that is entirely unique to cinema. Photography, writing, performance, music — all of those exist on their own in other mediums. But editing requires cinema and vice versa. Sure, there are other art forms that utilize sequencing and juxtaposition, but the act of the montage, manipulating time and space, is purely a filmic invention. I’m not an academic, but a term like “Pure Cinema” might be a useful phrase to describe what excites me the most — sound, movement, color, all spliced together by an editor into a continuous stream of light that miraculously conjures human emotions. That’s why, to me, the best filmmaking is indebted to strong editing.

Don’t Look Now, directed by Nicolas Roeg, remains one of the most influential pieces of so-called “Pure Cinema” from the 1970s. So naturally it has some of the best editing in the history of the medium. Graeme Clifford cut the film, joining the project at the behest of Julie Christie, with whom he had worked as a second-unit director on Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller. (Clifford also collaborated with Altman on the masterful Images and the supremely underrated That Cold Day in the Park.) After cutting Don’t Look Now, Clifford would work again with Roeg on The Man Who Fell to Earth and eventually went on to direct films himself, most notably Frances and Gleaming the Cube, which features one of the best angst-ridden skateboarding montages in cinematic history.

For those who are unfamiliar with Don’t Look Now, I urge you to rent or buy the recently released Criterion Blu-ray immediately. Here is the plot summary from Wikipedia, which doesn’t entirely do it justice: “Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland star as a married couple who travel to Venice following the recent accidental death of their daughter, after the husband accepts a commission to restore a church. They encounter two sisters, one of whom claims to be clairvoyant and informs them that their daughter is trying to contact them and warn them of danger. The husband at first dismisses their claims, but starts to experience mysterious sightings himself.”

A few years ago, I was asked to participate in an ACE (American Cinema Editors) event at the DGA Theater. It was a lively panel discussion where a group of us were asked to present a film clip that heavily influenced us as editors and discuss the reasons why. The choice for me was obvious: the opening sequence of Don’t Look Now, an absolute master class in cinematic montage and atmosphere. Contained within that first seven-and-a-half-minute sequence are all of the visual motifs, themes and obsessions that propel the rest of the movie. Roeg lays them all out for us, and he does so expertly, with very little dialogue, focusing almost exclusively on gestures, rhymes, and the elastic nature of time. If you look closely, you can see how this sequence anticipates every scene in the movie, as if we the viewers are experiencing the clairvoyance ourselves. I’m going to attempt an examination of the opening sequence here to point out how sound, music, image and color can contain multitudes, and how editing is the art that gives it all meaning.

The opening title of the film comes from directly from the Daphne Du Maurier short story on which it is based (she also wrote The Birds and Rebecca, both famously adapted by Hitchcock). That story is so named because it opens with the line “Don’t look now,” John said to his wife, “but there are a couple of old girls two tables away that are trying to hypnotize me.” In the film, I think the title functions differently, becoming more about the nature of sight and seeing. The title appears over a shot of rain and water, the first element to which Roeg will return again and again.

Roeg’s directing credit comes over a shot of a covered window, juxtaposing the roiling water with the ornate architecture of Venice. This is the first instance of circles, a second visual theme that emerges, as well as the obstruction of light — or the lack of seeing.

The first non-title shot reveals a little girl in a red rain slicker pushing a wheelbarrow through a field. Both the color red and the rain jacket itself will appear over and over again in the film. The white horse running wildly up the hill in the background has always seemed very odd to me. I sort of think of it like a ghost or a spirit — perhaps another premonition of some kind. Pino Donaggio’s score for the opening is kind of a lullaby, but played haltingly on the piano, as if by a child. This musical theme will return again at key moments, both during the famous sex scene and the bloody, unsettling climax.

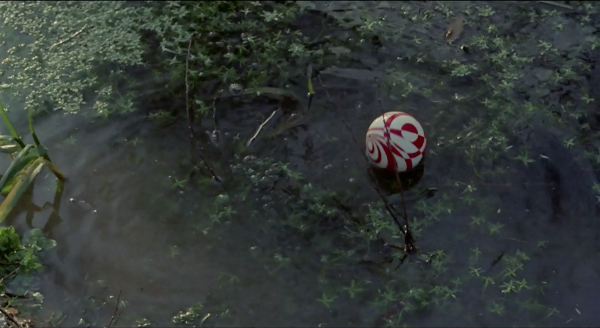

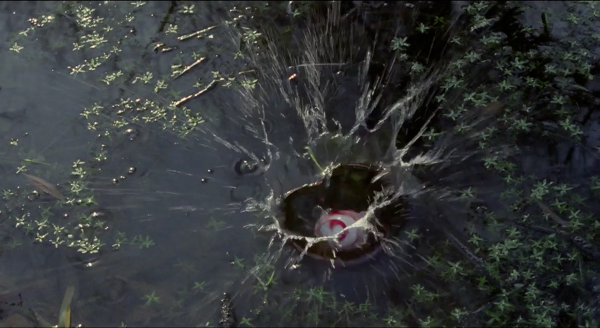

The little girl, Christine, emerges from an orange sun flare and we see her face for the first time. She throws a round, red-striped ball into a murky pond.

The ball splashes and then floats there for a moment, like the earth floating in the darkness of space. The image seems simple at first, even playful. But later on this ball will come to represent something much more ominous.

Roeg cuts to a little boy riding his bike through the beautiful yard of this ample British estate, dragging a stick. This is Johnny, Christine’s brother.

Wanting to retrieve the ball from the pond, Christine walks out across this little wooden bridge. The image of bridges will return again when the story moves to Venice, a labyrinthine city of bridges and water.

Roeg cuts to a reverse shot as Christine stares into the water, unable to retrieve her ball. Here, the house is revealed in the distance for the first time. I love how the little dollhouses are lined up on the bottom of the frame, mirroring the larger house. Houses and architecture will become important later in the film when Donald Sutherland’s architect character is tasked with the historical renovation of an old Venetian church. Incidentally, this scene takes place on a Sunday, pointing to the religious tension between this secular, intellectual couple, and the Bishop in charge of the church. It also underscores the themes of death and resurrection.

The shot of the house leads us inside, where we meet John and Laura. We start with a close-up image of the fire. As it zooms out, we see John immersed in his slides, examining images of an old church. We assume John and Laura to be the parents of the little boy and girl. In a way, they seem like older mirror images of them, but consumed with adult things.

The church slides seem innocuous at first, but upon a closer look, there is a strange figure wearing a red rain slicker similar to Christine’s. John turns to Laura, who is paging through a book. “What are you reading?” he asks. She explains that she’s looking for an answer to a funny question that Christine was asking earlier: “If the world is round, why is a frozen pond flat?” Even in this seemingly throwaway dialogue, we’re getting meaningful symbols — the pond, water, and roundness. The “frozen” aspect also conjures up images of glass, or mirrors.

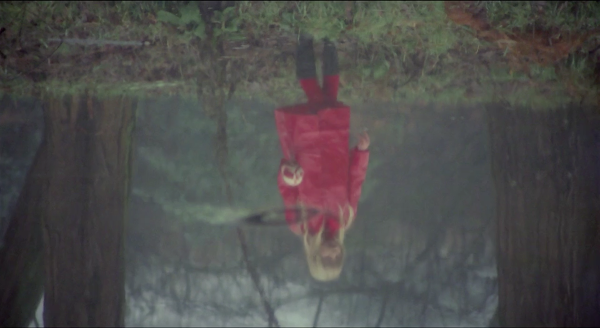

When we cut back outside, we see Christine in a reflection. She has somehow retrieved her ball and is approaching the pond again. This reflection will later be important when John first sees the strange, hooded figure wandering around Venice. He first catches a glimpse of this mysterious figure reflected in the canal water.

Christine splashes in a puddle, running left to right…

Which makes for a perfect match cut to Johnny — riding right to left, as he rides his over a piece of glass, shattering it and crashing his bike. Glass and water, reflections and surfaces…

When we cut back inside, Laura has found the answer to Christine’s question: “Lake Ontario curves more than three degrees from its easternmost shore to its westernmost shore.” To which John replies, “Nothing is as it seems.” Roeg has said that this last sentiment is the theme of the entire movie. Nothing is as it seems. As if to say, look closer — the answer is always below the surface. The earth is round (like the ball) and what appears to be flat, like time, might actually be a circle.

Laura asks John to pass her the pack of cigarettes, ever so slightly touching her mouth as she does so.

That makes yet another perfect match-cut to Christine, also touching her mouth. In this tiny moment, mother and daughter are connected across space and time — a shared history and love revealed in a simple gesture.

Johnny spins the tire on his bicycle to remove a piece of broken glass. Round things, glass — are you starting to see a pattern developing here? At the same time, this sharp object introduces a sense of menace into the scene. We begin to wonder, is Johnny really the one in danger?

John tosses the cigarettes to Laura…

Which match-cuts to the ball splashing into the water…

At that moment, the cutting begins to get faster — John abruptly knocks his glass onto the slide tray, spilling water all over his pictures…

As he looks closer through the magnifying glass, he sees that some of the water (or is it blood?) has spilled onto a slide…

It oozes all over the image of the church, pooling next to the strange, hooded figure sitting in the pew…

In this moment, John senses something is terribly wrong. The idea of extrasensory perception (or ESP) comes into play later in the film when the blind psychic tries to “hypnotize” John in the Venetian café. Blindness, or the lack of seeing, is contrasted with the ability to see beyond normal perception — to see into other worlds, across space and time.

John runs out the door of the house on instinct, unsure why he’s even doing it…

Where he finds Christine sinking into the pond…

Johnny looks on in horror, holding a piece of glass, his hand now cut and bleeding — is this the same blood we saw on the slide?

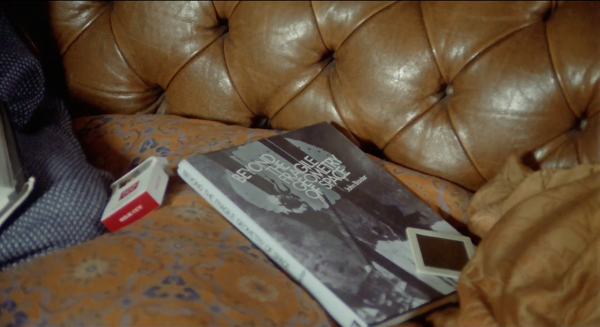

We cut back into the house where Laura is totally unaware that her daughter is drowning. She puts the book down that she has been reading: Beyond the Fragile Geometry of Space. Indeed.

The liquid on the slide begins to turn blood red, growing and mutating. The music takes a drastic turn, transitioning from the lullaby into a dark and foreboding dirge. Heavy drones and brass swarm the soundtrack.

John lifts the drowned Christine out of the water. Extreme slow-motion and a series of jump-cuts simultaneously expand and compress time. Donald Sutherland’s horrifying guttural moan tears a hole in our heart. Apparently, this part of the sequence was actually shot on a soundstage so that Roeg could more precisely control the look and lighting (as well as the temperature of the freezing water).

As Laura steps outside and comes upon the awful scene of her daughter’s death, she lets out an awful shriek. Notice the red flowers behind her, as well as her hand gesture, both rhyming with previous images of Christine. The audio of Laura’s scream seems to transcend time. It doesn’t perfectly sync with the picture, and it goes on for way too long. This moment smash-cuts brilliantly to a shot of a drill boring into the concrete foundation of the church in Venice, perfectly bridging time and space through a deafening sound effect.

Many others have looked at these scenes and found different elements to explore. That’s why it’s such a rich, amazing piece of filmmaking. This sequence was shot separately, in England, before the production moved to Venice. It works both as its own self-contained film and as perfect foreshadowing to John’s attempted “rescue” of the mysterious hooded figure at the end. It remains an amazing example of cinematography, music, performance and especially editing.